Last revised May 26, 2023.

Table of Contents:

- Agawa Rock – A Must Visit and How To Get There

- The Trail From The Parking Lot To The Shore

- Selwyn Dewdney and Rock Art Research

- Shingwaukonse’s Sketch of Some of the Site’s Images

- An Overview of The Pictograph Site

- Thor Conway and Spirits On Stone

- Panel I – Sturgeon and horned snake images

- Panel III – Myeengun’s War Party”

- Panel IV – canoe with two paddlers

- Panel VI – Moose

- Pane VIII – Mishipeshu, Snakes, and Canoe

- Panel IX – canoe with three tall human figures

- Panel X – The Horse and Rider Panel

- Panel XII – the two bears

- Panel XIII – canoe and Woodland Caribou

- Panel XIV – The Two Drummers

- Panel XV – canoe with two paddlers

- Not All Visitors Are Respectful – Fresh Graffiti

- Sources For Further Research

See Related Posts in the Anishinaabe Rock Images Folder.

—————

Agawa Rock – A Must Visit and How To Get There

Images expand with a click; blue text leads to additional information with a click.

Easy to access – but easy to miss!

As you’re driving along the Trans-Canada Highway (Hwy 17), either 80 kilometres from Wawa heading south or 150 kilometres north from Sault Saint Marie, you will pass by a sign indicating that the turn-off for Agawa Rock is coming up soon.

The sign will probably not even register with most travellers, unaware that they are passing by one of Canada’s most significant pictograph sites where rock paintings made by Anishinaabe shamans two or three hundred years ago can still be seen. Most similar sites on the Canadian Shield require a canoe or a boat and a bit of time to get to. This is easy!

The sign will probably not even register with most travellers, unaware that they are passing by one of Canada’s most significant pictograph sites where rock paintings made by Anishinaabe shamans two or three hundred years ago can still be seen. Most similar sites on the Canadian Shield require a canoe or a boat and a bit of time to get to. This is easy!

Turn off Highway 17 and on to the access road for Agawa Rock for a two-minute downhill ride to the parking lot. There you’ll need to get a machine-generated permit for $5.25 which gives you two hours on the site. Another ten minutes of walking on a sometimes-rocky trail down to the shores of Lake Superior and you are there.

There is another option if you want to paddle up to the pictographs – you can drive down to Sinclair Cove instead of turning in at the parking lot. Down at the cove is a boat launch and you can put in there. You also get to visit what was once a campsite popular with the voyageurs of old as they made their journey to the west end of the lake. If the waters are calm – which is often not the case! – the canoe option would give you a different perspective of the site as you framed some shots in your camera viewfinder.

What follows is a selection of photos my brother and I took during our two visits to Agawa Rock. We first visited in August of 2013 after a Wabakimi-area canoe trip; waves and high water meant we were only able to see the first third of the site. This summer on our return from Red Lake and our Bloodvein River canoe trip we had better luck and were able to walk the length of the ledge accessible to the public.

—————

The Trail From The Parking Lot To The Shore

At a couple of places on the side of the trail to the pictographs, you’ll see a sign like the one below. The warning should be taken seriously – a walk on the ledge in rough weather is no place for even the most sure-footed adventurer to be. A pic a bit further below shows what it was like on our first visit – i.e. mostly inaccessible.

On our second visit, we had better luck as the water in the above image shows.

——————————–

Selwyn Dewdney and Rock Art Research

At the bottom of the hand railing, the first thing you see attached to the rock face is the following plaque –

While the site was obviously known to the Ojibwe and cottagers of the area, it was Selwyn Dewdney whose inclusion of the site in his book Indian Rock Paintings of the Great Lakes brought the pictographs back into the discussion of Anishinaabe culture and spirituality.

That is Dewdney on the right side of the image below, with his friend and fellow artist Norval Morrisseau in the middle. Jack Pollack, the Toronto art gallery owner who hosted Morrisseau’s first-ever show in 1962, is on the left. See the following post for more on the Morrisseau-Dewdney relationship:

Selwyn Dewdney, Norval Morrisseau, and the Ojibwe Pictograph Tradition

Selwyn Dewdney, Norval Morrisseau and the Ojibwe Pictograph Tradition

Shingwaukonse’s Sketch of Some of the Site’s Images

Dewdney visited the site for the first time in 1958, having picked up on the existence of the site from the notes and drawings made by Henry Schoolcraft in the mid-nineteenth century. Schoolcraft worked as the Indian Agent at the Sault Ste. Marie on the U.S. side. It was his collection of Ojibwa legends that formed the basis for Longfellow’s epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, mistakenly named after a 16th C Iroquoian leader instead of the Ojibwe Manabozho, the name Longfellow decided not to use!

In 1851, as Dewdney recounts it in his book, Schoolcraft “published his Intellectual Capacity and Character of the Indian Race. Included in it were birchbark renderings of two pictograph sites painted by an Ojibwa shaman-warrior who claimed the special protection of Mishipizhiw…” (Dewdney, 14)

The birchbark renderings of the Agawa Rock pictographs that Dewdney referred to were drawn by Shingwaukonse.

See here for the rest of the Wikipedia article on Shingwaukonse. (The first part of his name is also spelled Chingwauk and literally means “Pine” in Ojibwe. See here for the Ojibwe dictionary entry. The onse ending indicates “little”.)

The Canadian Encyclopedia has a more detailed account along with a list of suggested additional sources. See here.

My recent Chiniguchi/Sturgeon canoe trip report has a section which deals with Shingwaukonse’s significance in the context of the Robinson Treaties of 1850. See here.

Here are drawings of some of the Agawa Rock images that Shingwaukonse made for Schoolcraft in the late 1840s.

This, then, was the information that Dewdney had as he tried to track down the site. Here is his account of the day he finally found it-

The rock ledge runs along the length of the 100-foot high granite cliffs here; you can imagine the original painters standing there and putting their ochre/fish oil “paint” to the rock face. Motivated by vision quests or the placating of turbulent spirits of the lake, a succession of painters all left their mark. It was not uncommon for one generation’s pictographs to be painted over by the following generations.

——————————–

Thor Conway and Spirits On Stone

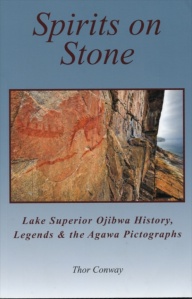

The ultimate source about the Agawa Rock site as it exists today is Thor Conway. His book

Spirits On Stone (the 2010 edition of a book first published in 1991) presents the pictographs in the voice of the descendants of the Ojibwe who painted them. Conway identifies 117 separate pictographs at the site and provides the most informed commentary I have found anywhere as to the meaning and purpose of these rock paintings.

Conway divides the site into seventeen different panels, with anywhere from one to eight separate pictographs in each of those panels. I have used his panel numbering system (from I to XVII in Roman numerals) to identify the pictographs we recorded.

——————————–

Panel I:

Panel I is the first panel you see as you step onto the ledge.

The horned snake is associated in Anishinaabe cosmology with the healing powers of the shaman or medicine man.

——————————–

Panel III:

This panel, attributed to an Ojibwe warrior named Myeengun (“Wolf”), apparently depicts a historical event from the late 1600s. It recounts the confrontation of the Anishinaabe of the area with an invading Iroquois war party.

Each of the canoes represents a local clan, with a crane, eagle or Thunderbird, and a beaver in front of one of them. Conway devotes thirteen pages to a discussion of the panel’s meaning. Drawing both from Henry Schoolcraft’s writings and from the memories of local Ojibwe like Fred Pine, he makes a good argument for this interpretation. (The drawing on the left is from Grace Rajnovitch’s book Reading Rock Art.)

Each of the canoes represents a local clan, with a crane, eagle or Thunderbird, and a beaver in front of one of them. Conway devotes thirteen pages to a discussion of the panel’s meaning. Drawing both from Henry Schoolcraft’s writings and from the memories of local Ojibwe like Fred Pine, he makes a good argument for this interpretation. (The drawing on the left is from Grace Rajnovitch’s book Reading Rock Art.)

——————————–

Panel IV:

Most of the pictographs are fairly small (from 5 to 15 centimetres in size) and many are all but indecipherable. Some visitors to the site are clearly disappointed with what they see. The site is definitely not the Lascaux Caves! It is a situation where some pre-visit research can help provide the background needed to bring out the meaning of what often needs to be drawn out of the rock.

——————————–

Panel VI:

——————————–

Panel VIII:

The most famous panel is Panel VIII – that of the Great Lynx or Panther (but looking awfully reptilian) whose moods account for the turbulence of the lake. Canoes will make safe passage – or not – depending on whether or not he has been properly acknowledged and placated. Living with him in the depths of the Gichi Gami (“Great Sea”) are serpents, two of which are depicted below Mishipeshu. One can only hope that the canoe behind Mishipeshu did not incur his wrath.

The image to the left is what Dewdney found in 1958 on his first visit.

initials and year # as it looked in 1958

Here is what he wrote in his book:

In her lack of understanding of what she was looking at, the girl had painted over what Conway calls the most famous aboriginal painting in Canada! The modern paint has clearly not lasted as these days there is only a little evidence of the black paint used.

A section of the Dewdney sketch – annotated by someone else?- focuses on what he labels Faces IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC. Conway used the term “panel” instead.

——————————–

Panel IX:

However, I’d soon find evidence that even today (imagine!) some unthinking people are unaware of or do not care about the impact of their actions.

——————————–

Panel X:

Panel X – the Horse and Rider Panel – is another dramatic set of pictographs. Seeing Conway’s rice paper copy of this panel which he made in the late 1980s, I am struck by the degree to which they have faded. No longer visible is the cross above the fourth sphere; gone too is the circle with lines emanating from it in front of the horse. It may represent the Megis shell which figures in the Migration Myth preserved by the Midewiwin, the select group of Ojibwe shamans.

See here for an analysis of The Mishipeshu and Caribou Panel at Fairy Point on Lake Missinaibi, which includes an image of a similar circle with a line in the middle and rays emanating from it. Yet another example can be found at a nearby pictograph site on Little Lake Missinaibi.

The human figure on the back of the horse is also much less clear than it was twenty-five years ago.

Apparently, the two arches at the bottom of the panel were once two concentric circles that encompassed the entire panel; the top part has flaked off in time and fallen into the lake. To the right of the panel are five horizontal lines, the meaning of which we will never really know.

As for the spheres, there are a couple of explanations. One has to do with the passage of time – a period of four days – to accomplish some unstated deed. Schoolcraft gives such an explanation. On the other hand, Conway related the spheres to the Midewiwin, the Anishinaabe society of shamans. With each sphere representing a level of power, the fourth level is the highest level of spiritual power attainable. Conway’s book, chapter 10 (“Secrets of The Horse and Rider Panel”), provides an explanation of his analysis.

[The images above from Conway’s Spirits On Stone (used with the kind permission of the author) illustrate two of the techniques used to record the pictographs. The earlier method made use of by Dewdney involved placing wet rice paper over the pictograph and then copying it. It was eventually replaced in the 1970s by the use of clear acetate and acrylic paint to copy the rock paintings.]

Barely visible these days is the cross whose base begins at the top of the fourth sphere and the canoe with a solitary paddler about halfway up on the left side.

——————————–

Panel XII:

——————————–

Panel XIII:

Further down the cliff face, you come across the following panel – a canoe with a human figure in it followed by two caribou.

——————————–

Panel XIV:

——————————–

Panel XV:

And that was it for our visit to the dramatic cliff face of Agawa Rock. There are a few other pictographs just a bit further but they are beyond public access. We turned around and returned for a last look at the two bears, the horse and rider, the Mishipeshu and snakes.

——————————–

Not All Visitors Are Respectful

Other than the almost-gone graffiti on the Mishipeshu panel from 1937, we also got to look at a couple of examples of recent acts of vandalism. The first was the painted initials in the image below.

More troubling were the new nonsense symbols scratched into the rock face with a key or some sharp object. They seemed very fresh, perhaps from 2014.

Usually, there is a park employee sitting at the beginning of the pictographs; sometimes though (s)he goes up to the parking lot to check for possible non-payment by visitors. In any case, there is no way to police the entire rock face 24/7. My school teacher’s answer is to make people aware of the significance of what they are looking at and of the impact of their actions to the point that they police themselves.

That, of course, is the theory – but damn, just look at the nonsense above. Lack of understanding, lack of respect, sheer ignorance – call it what you will. While it is only the latest bit of graffiti that Agawa Rock has seen, it is so fresh you can feel the scratches – and they hurt.

[If you have a more recent image of the above graffiti and would send it to me, I’d insert it here to show how it has aged since 2014.]

In time the above scratches – just like the paint but over a longer period of time – will fade away. And so too – unfortunately – will the remaining pictographs. Make sure you pay them a visit – you’ll need about an hour and a bit longer if you want to take in the atmosphere. The only thing you can’t control is the weather and the state of, with a nod to Gordon Lightfoot’s song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”, “the lake that they call Gitchi Gumi”!

Otchipwe-kitchi-gami ….the big sea of the Ojibwe people

——————————–

Sources For Further Research

Recommended before or after a visit to the site is some time spent checking out these three classics of Ojibwe rock painting research in Canada. Just click on the title for access to the book itself – or for info on how to get it.

—————-

- Selwyn Dewdney. Indian Rock Paintings of the Great Lakes, especially p, 77-83.

—————-

- Thor Conway. Spirits On Stone: Lake Superior Ojibwa History, Legends & the Agawa Pictographs. 2010. Second Edition. 132 pages. While I ordered my copy directly from the author, I also did see a half-dozen copies of the book available at the Lake Superior Provincial Park interpretative centre a few kilometres south of the site at Agawa Bay. Click on the title above to access Conway’s site or here for Amazon.ca.

—————-

- Grace Rajnovitch. Reading Rock Art. 1994. Seven of the 143 figures and illustrations in this book are from Agawa Rock, which also gets frequent mention in the text. The book is recommended to anyone keen on understanding more deeply the Anishinaabe culture behind the pictographs. Rajnovitch makes major use of the illustrations and text of the Ojibwe birchbark scrolls in her bid to “read” the rock art.

—————-

If you’d like more information about other rock painting sites of the Algonkian Peoples of the Canadian Shield, the folder “Anishinaabe Rock Art” found on my blog header has a long list, including these two to get you started!

—————-

Anishinaabe Pictograph Sites Of The Canadian Shield

Anishinaabe Pictograph Sites In Ontario

I wonder what they used for paint. Also, how has it lasted by the water (agawa rock) for so long, and why has it faded so much in the last 25 years?

Thank you.

Kirk, re your question –

The “paint” used by the Ojibwe shamans to put their images onto the white granite rock face was called “onamin” or “wunnamin”. This substance was a mixture of at least two ingredients. First, they turned pieces of ochre-coloured hematite or ferric oxide into a fine powder. Then they mixed it with fish (often sturgeon) glue and oil. This was the paint they used.

This mixture of mineral and organic substances seems to bond with the rock over time. As well, the painted images get covered over time with a thin layer of mineral or what Thor Conway calls “rock veneer” dripping down from above in the rainwater. After a while, the onamin “paint” is no longer exposed directly to the elements,

Ojibwe myth provides us with another explanation of the origin of the red pigment. Norval Morrisseau’s Legends of My People The Great Ojibway includes an account of an epic struggle between Nanabush and a Giant Beaver who had constructed a dam blocking the water from leaving Lake Superior (Gitchi Gami). In the end, the beaver was killed and his blood was sprinkled all over the area. It is this blood that shamans use to draw the images on the appropriate rock faces. Here is a Norval Morrisseau painting from 1978 which illustrates another version of the myth – here it is Thunderbird and not Nanabush doing the killing.

A safe guess is that the pictographs that are still discernible were painted between 150 and 400 years ago. The evidence does not support claims that the ones we can see date back 5000 years or 2000 years. This does not mean that pictographs were not part of some cultural tradition way back then; it just means that those images have faded away, perhaps to be painted over by newer images.

It is entirely likely that all the pictographs I have seen in my paddles will be gone in fifty or a hundred years. You’re right about the noticeable change just in 25 years. The fading and blurring – not to mention the breaking off from the rock face of entire slabs of the rock as I saw at the major site on Artery lake this summer – like all things in this world, pictographs have a limited shelf life.

Amazing, so beautiful~~~mahalo.

Josephine, miigwetch!

Agawa Rock is a special place. I’m glad my post captured a little of that.

Some day I hope to visit and see these pictures. What a fantastic find. I live for evidence like that, of people’s dreams and ideas long ago, living in a time I also dream about.

Hopefully you can mount some sort of camera, or at least a sign on the paths saying there’s a hidden solar-powered camera on the pictograph area catching any who molest it which will lead to a huge fine.

Thank you for compiling all of this wonderful data and photos of the Agawa Rock! I recently visited a few weeks ago and was thrilled to see Mishepeshu again! He also makes an appearance on the Sanilac Petroglyphs here in my home state of Michigan.

Even though I have only visited this area of Canada twice before in my life this was my first visit to Agawa Rock, and the whole trip felt as if I had come back “home” for a visit.

Alison, there are more than a few pictographs sites on the U.S. side that I’d love to get to! So much to discover!

Miigwetch for sharing! I’m in my first year of University and plan to take anthropology or geology next year! It really warms my heart of how much passion you put into this research and anishinaabe culture. I am ojibwe and I am so excited to buy your books! 🙂

Tyra – you’ve picked my two favourite areas of study – human culture and Mother Earth! When I was 18 (back in 1969!) I started my work on a degree in World Religions – I could easily have picked anthro as my field of study! And on my canoe trips I find myself wishing that I had picked geology so that I could read better the story of the rocks and landforms I am paddling by. Reading books, reading people, reading rocks! A geologist is just practising a different kind of literacy!

As for the pictographs, they need a new generation of Anishinaabe and others to care for and about them. A miigwetch back to you for your positive review of my post! May your studies take you on a great journey!

Pingback: Great Lynx, the Thunders, and the Mortals – Mii Dash Geget